The

Surge to Merge Culture with the Economy

Copenhagen Free University, 29th September 2001

Good evening.

Firstly I want to thank Henriette and Jakob for inviting me to speak here at the Copenhagen Free University. I'm going to start with a clip from an arts programme made by Bloomberg TV called 'The Finer Things' from March 2000. I'm not sure of the broadcast date but it's a very quick and very funny introduction to some of the points I want to raise this evening.

· Video: Video:

Bloomberg TV, London 'The Finer Things' March 3, 2000. Broadcast date

unknown. 90 second clip featuring London based artist, Clem Crosby. From

the archive of Johnny Spencer

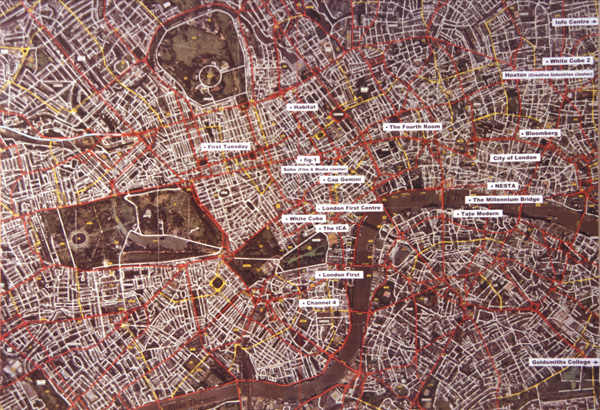

· Panel: Overhead view of London: Tate Bankside, City of London,

Bloomberg, Habitat, London First, the London First Centre, White Cube,

fig-1, The Club, The ICA, Channel 4, Goldsmiths, NESTA, Cap Gemini, Info

Centre, Soho and Hoxton clusters etc.

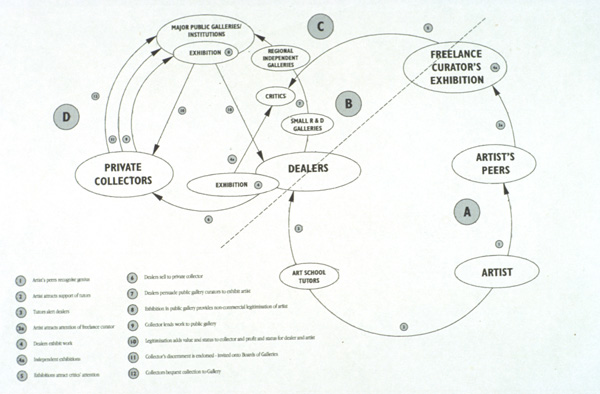

...I'm going to ignore the "explosion of talent" bullshit for a moment and concentrate on the London question from a different set of co-ordinates. Here, we have an overhead view of London (large panel) in which I've highlighted some of the organisations that I'm going to talk about this evening. This form of mapping is just a useful tool for me to show the link between contemporary art and other sectors of the economy. I've included City of London organisations, creative industry clusters, companies, public institutions, galleries and other points of reference that, I hope, will illustrate what Colin Tweedy, the Director of Arts & Business, has referred to as the "surge to merge culture with the economy" (Sunday Times, Oct 19, 1997).

I should start by saying that this talk is based on a series of articles that were co-written with Simon Ford over a three year period from 1997 to 2000. To be honest, some of the material now feels a bit dated, in some cases glaringly obvious, and in others over-determined. With this in mind I'm going to focus on how the surge to merge has radically transformed the landscape in which artists, curators, writers, and many others now operate. I'm also going to suggest that the convergence of economic, political and cultural agendas can be seen within the context of structural change in the corporate sector. We've moved into a world where contemporary art plays an increasingly key role in the 'new' informational economy and public institutions, for example, now act as networking clubs for venture capitalists and cultural entrepreneurs.

In order to understand this activity and its impact on culture I'm going to look at how networks and 'new' economies are formed, accessed and utilised – and where they converge, interact and disperse.

· Slide: Sensation

exhibition opening, The Evening Standard, Sept 1997.

This slide is from a newspaper feature on the opening party of 'Sensation' at the Royal Academy, London, in September 1997. On the right hand side we can see Michael Heseltine, former Conservative government minister and on the left Nick Cave and Sophie De Smirnoff. It was a typical art opening at a prestigious gallery, with business executives mixing with politicians, aristocrats, pop stars, broadcasters, and artists. A thriving and internationally respected art scene is important both symbolically and economically. It is the avant-garde of the other creative industries of fashion, music and design; an area of outrageous research and speculative development.

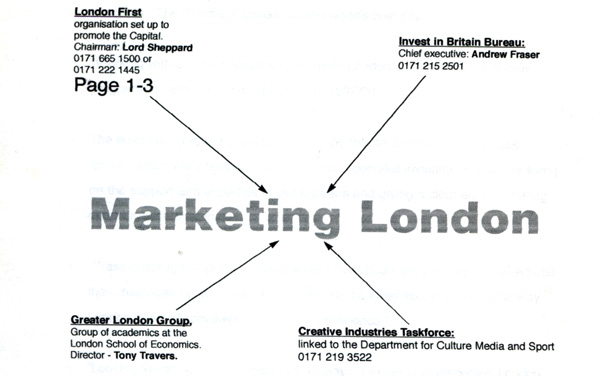

· Slide: 'Marketing

London'. Working diagram, A.Davies & S.Ford,

Art Capital, 1997.

When Simon and I first started research in this area we wanted to find out if there was a link between the promotion of London as the 'coolest city on the planet' (Newsweek, Nov 1996) and what the financial press were calling the financial services 'gateway to Europe'. So we shifted our research on to some of the organisations that had been set up with the aim of promoting London. These included Central London Partnership with its 'envoy programme', the Joint London Advisory Panel (set up in 1995), the Invest in Britain Bureau (1977), the Greater London Group (1998) and the London First Centre (1992). To give you an idea I'll briefly quote from the 1996-97 London First Annual Report – in 1996 London was 'the world's most popular City', 'the top European location for doing business', 'the Millennium City', 'the City for Europe' and 'the global hub'. The success of these organisations can be measured by the fact that towards the end of the 90's the UK accounted for 40 per cent of Japanese, US and Asian investment in the EU.

Culture was very much part of the marketing mix that, within the context of the European Union, kept London ahead of its competitors, principally Paris, Frankfurt and Berlin. It was a less tangible, but important factor for top executives making decisions about where to locate businesses. As Tony Travers, director of the Greater London Group, summed it up at the time, it's all about reflected self image: "Decision-makers want to be living and working in places which reflect well on them." (Alison Warner. 'Capital working city'. Financial Times, Nov. 27, 1997).

One of the many myths surrounding London's spectacular cultural renascence in the mid to late 1990's was that it developed without the help of state funding. In addition to the Department of Trade and Industry and the organisations that I've just listed, 'Swinging London' was heavily dependent upon a variety of State agencies, from the London Arts Board through to the international exposure given by British Council supported exhibitions. Young British art, as is apparent from its title, was promoted as a national art movement and this is why the British Council, a publicly funded organisation set up to promote British culture abroad, was so forthcoming in funding exhibitions and travel. During this period artists (and many other representatives from the Creative Industries) were utilised as cultural ambassadors to represent, and most importantly redefine, 'British' culture to an international audience. The young British artists (along with the British workforce as a whole) were promoted as entrepreneurial, resourceful and independent – very much in line with the global positioning of a market-friendly 1990's Britain. In this respect, young British artists were called upon to camouflage increasing social division and inequality at home through the promotion of a rejuvenated entrepreneurialism abroad.

In the first strand of this surge to merge we can see cultural, political and economic agendas converging in the promotion and global positioning of a City (with full support from the resident business community). This activity underpinned the rise of young British Art and the spectacular emergence of London as the coolest city on the planet.

It's within this context that I want to look at another aspect of the surge to merge culture with the economy – the impact of corporate restructuring on contemporary art and the cultural sector in the UK. I'm going to start with a quote from a recent company brochure which for me, illustrates an important shift in corporate strategy over the last decade and may go some way to opening up debate on a number of issues that have recently surfaced in London ... and I'm sure here in Copenhagen.

"A company is no longer really a place: it is becoming a network to which its people, its world must remain connected. Its main lever of growth is its inventory of skills and its ability to deploy them in different markets". (Cap Gemini Annual Report)

Company networks now intersect the public and cultural spheres in increasingly complex and varied ways; even sponsorship is not quite as straightforward as it used to be. In a period dominated by cross sectoral activity many companies have actively sought alliances with other sectors, particularly cultural institutions in the public sector. This has been further compounded by funding and structural constraints and a prevailing view that publicly funded institutions are ill equipped to deal with a rapidly shifting and convergent culture.

The realignment between the public and private sectors can be seen in the sponsorship debate as it moved from a 'hands off' to a 'hands on' relationship with cultural events and programming in the late 1990's. The so-called 'marriage made in heaven' where companies would simply pay to be associated with an event, exhibition or performance is now seen as one of many options. Of course companies still pay up but now many want something in return. These 'returns' can be linked to social and ethical responsibility, reflected self image, extending networks, building customer databases, training personnel (Arts & Business' pairing scheme), knowledge transfer, access to the wider community, and more recently, 'corporate empathy', UBS Warburg's hilarious take on the mutual impenetrability of contemporary art and business (UBS Warburg and the British Council Collection 'Brit Art' exhibition catalogue, March 2001).

· Slide: The Habitat Art Broadsheet promotion. Ben Weaver and Carl Freedman, 1996.

In London we can see these 'returns' or new forms of company involvement emerging in the retail sector in the mid 1990's as Habitat (the retail furniture company), Emporio Armani, Harvey Nichols, Browns, Levis and many other stores set up artist programmes.

In 1996 an alliance between Habitat and the Observer Media Group plc formed around the Habitat Art Broadsheet with the aim of building a joint customer database for marketing purposes. The database was partly made up of names collected through subscriptions to the Broadsheet and its invitation lists to in-store exhibitions. This strategy was linked to 'relationship marketing' where customers would trade information about their income and lifestyle in return for special offers and 'loyalty cards'. The team at Habitat, headed by Ben Weaver (press office) and Carl Freedman (independent curator) sold the project to artists as an opportunity to reach new audiences – an alternative to the elitist gallery system that would enable contemporary art (and I quote) "to participate in everyday life" (Habitat press pack, November, 1996). In this case, 'participation in everyday life' would have been courtesy of Habitat's customers/employees and the major feature articles published in The Guardian and Observer. This type of media attention also reflected the growing integration of art with the other so-called 'creative industries'.

· Slide: 'Art Goes Home'. Posterstudio strategy diagram. November 1996.

An internal memo outlining the aims and objectives of the Art Broadsheet promotion formed the basis of a presentation at Posterstudio in 1996. Posterstudio was a self-funded project space in central London that developed in two phases over a three year period in the mid 90's. (Poster Studio, 1994 – 1996: Merlin Carpenter, Dan Mitchell and Nils Norman. Posterstudio, June 1996 – May 1997: Anthony Davies, Chris Saunders and Dan Mitchell). The 'Art Goes Home' project was a counter forum that coincided with the press launch of the Habitat spring/summer collection in November 1996.

This diagram simply sets out points of contact and dispute. Very briefly, the aim was to open up a space in which the target community (in this case participating artists and consumers) could discuss some of the more complex social and economic aspects of the Habitat programme. The Posterstudio team interviewed participating artists, looked at the economics – in this case the system of artists payment, the company's savings on advertising and marketing budgets, its aims and objectives, the convergence of art and commerce through lifestyle media, etc. They also tracked down the M.A. thesis of the programme's architect (Ben Weaver) and analysed the sliding scale of artists fees – with the first batch of yBa notables receiving £2000 and the less notables receiving (and I quote from an interview with a less notable) "£200 and a wicker chair".

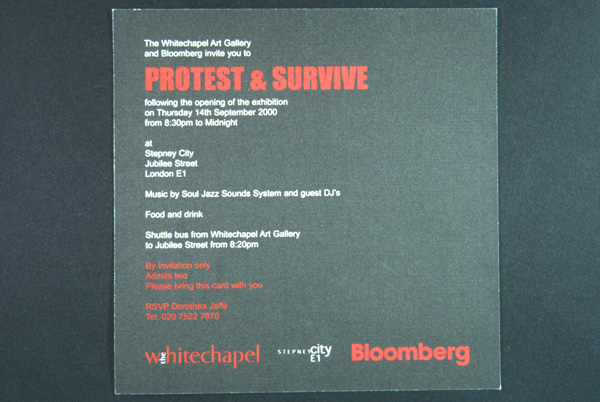

· Slide: Sponsorship

slide. Protest and Survive, 2000.

Other forms of involvement occurred as companies started to move towards an integrated partnership or alliance strategy. This marked a further shift from the 'something for nothing' arm's-length philanthropic model to a 'something for something' contract in which marketing departments started to perceive cultural (and often social and environmental) programming as an integral part of their ethical marketing strategies. As Rick Little from the Global Alliance for Workers and Communities recently noted, "being involved in the wider community gives the company greater prominence in the same way that advertising does". (Michael Skapinker, 'Philanthropy during a downturn', Financial Times, 27 April 2001). In this sense, some companies have become more strategic and this can be seen in the shift in terminology regarding arts funding – away from 'sponsored by' towards 'in partnership with', 'in association with', 'in collaboration with' and 'co-produced by'. In many respects, this is indicative of a new agenda based on alliances and what looks like an increased corporate decision-making role in cultural programming.

So, just to quickly recap – in the second strand of the surge to merge we see companies forging closer economic and promotional links to contemporary art/culture. This activity was further compounded by corporate restructuring, cross sectoral alliances and large companies and rich backers buying "into people they see as working on the cutting edge of culture ... because they need to be seen as part of that culture." (John Warwicker quoted in The Guardian, October 27, 1997).

Finally, I want to look at new and complex forms of organisation, namely post-gallery, post-institutional alliances, which are cross sectoral and not necessarily linked to a specific location, economy or discourse. In this sense they can be seen to mirror the corporate model that I quoted earlier...

"A company is no longer really a place: it is becoming a network to which its people, its world must remain connected...".

All are knowledge and network based and include artists, writers, curators but unlike galleries and cultural institutions, they are not linked exclusively to the production, legitimatisation and distribution of art.

We can draw a parallel to these 'knowledge-based' networking models in the corporate sector with First Tuesday and the Fourth Room. First Tuesday was the market leader of matchmaking clubs for internet entrepreneurs and venture capitalists before it collapsed earlier this year. The Fourth Room is a hangout zone for corporate executives and other 'leading individuals'. In return for a £10,000 per annum fee, members receive a weekly in-house publication and an opportunity to eavesdrop on "emerging cultural trends and monitor changing patterns and beliefs". (The Fourth Room company brochure, 2000). As Piers Schmidt, co-director of the Fourth Room claims, "it's all about collaboration" and to this end the aim is to get CEO's mixing with eco-activists like Swampy over breakfast.

· Slide: Cap

Gemini/ICA Imaginaria invite, 1998.

And now onto the ICA. The Institute of Contemporary Arts in London, a publicly funded institution, has over the last 2 years forged closer links with companies and looked at new ways of financing culture. Simon and I were first drawn to the ICA around the Imaginaria Award in 1998-99. There were a couple of points of interest – the first was the list of selection criteria handed to the judges, and its relation to Cap Gemini's global marketing position. Cap Gemini, now Cap Gemini Ernst and Young, is one of the world's largest management consulting and computer services firms and, as such, would have had a direct investment in supporting and rewarding practices that were seen to engage (and I quote from the brief given to judges) "a dialogue between the scientific, corporate and the artistic (striving) for a new perspective..." (Cap Gemini/ICA Imaginaria judges criteria, 1999). I should just add that, in addition to artists, the award was open to scientists, technologists and 'people from the business world'.

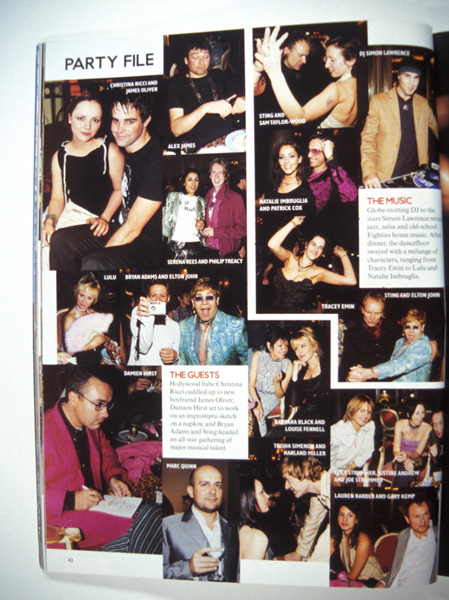

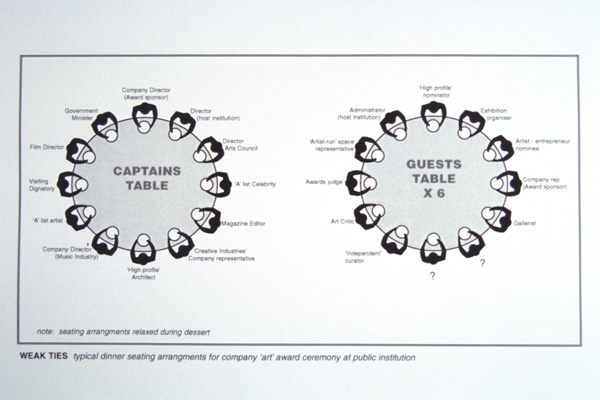

· Slide: Dinner

table seating arrangements from the AA report, 1999.

Oddly enough, our main point of interest was the seating arrangement for the dinner party and the breakdown of the invited guests. It was a roll call of key players in the creative industries and other related sectors; government ministers, celebrities, architects, businessmen and so on. In addition to 'reflected self image', association and other benefits linked to sponsorship there were other, hidden factors. These included the mutual benefits of a perceived temporary partnership between Cap Gemini and the ICA, their role as network captains (bringing sectors together), the symbolic linking of 'cutting edge' culture to business and accessing the digital arts community and its networks in the UK. In this sense Imaginaria can be seen as a successful partnership and effective network busting exercise for both organisations.

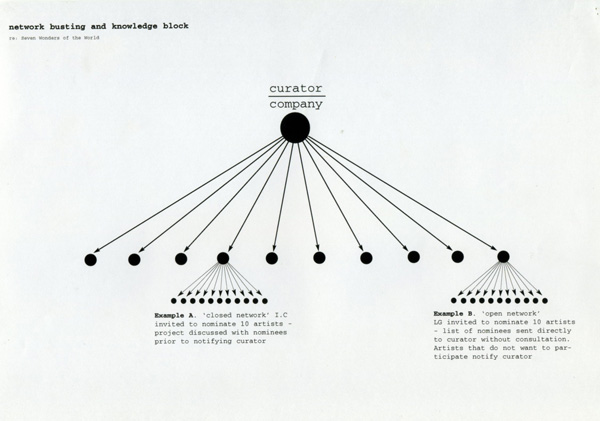

· Slide: Network-busting

diagram, 1999.

(Verbal aside: on how curators and companies access and exploit social networks)

· Slide: Diagram

– dinner table abstract, 1999.

Someone joked to me recently that the only organisational aspect of cultural events that interest large companies are the parties. What he didn't go on to say was that the party is very much a central feature of cultural programming. It's the field in which essential face-to-face social contact takes place and in this respect the ICA now seems to have dispensed with the networking pretext (the exhibition, awards, the object) altogether and evolved into the first of my three models – the members only networking club...

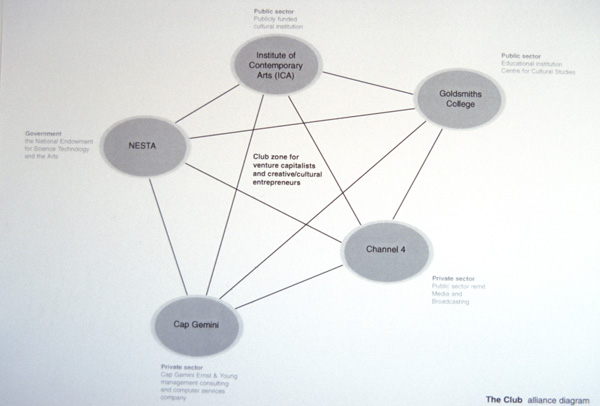

· Slide: The

Club diagram, 1999.

The Club was set up by the ICA in conjunction with Goldsmiths College, the National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts (NESTA) Channel 4, the Arts Council and Cap Gemini. It is a networking club for cultural entrepreneurs and, initially at least, educationalists, arts administrators, television executives and business consultants. It's an invite-only monthly event that provides "a networking base for its members" and promises to introduce them to agencies, from television companies to venture capitalists and private organisations, who may wish to support and commission them. (The Club, email to members, July 2000).

It's extremely difficult to locate the mutual bonds and orientation of The Club, but it's a good example of an emerging inter-organisational network that may in this case represent the initial stages of a corporatised future for UK cultural institutions. This falls in line with current UK government policy, which aims to refocus its funds into promoting enterprise, small business and knowledge transfer and to "concentrate on managing change rather than attempting to direct companies' activities." (Kevin Brown, 'DTI allocates extra funds to boost enterprise', Financial Times, July 17, 2000)

When Simon and I first started looking into The Club in July/August last year we had difficulty getting anyone to agree to talk to us: we were told that the whole thing was, and I quote, "at an embryonic stage". As a result most of our information came from a press release to members, telephone conversations with the press office and participating artists. Now that it's a fully-fledged model and has been carefully filtered into the public domain (via the Financial Times) it might be possible to speculate a bit further.

There are still areas of confusion – organisations that in the press release were credited as collaborators, for example, have become co-sponsors and this very much falls in line with the subtle shifts in terminology that I outlined earlier. Is Channel 4 actively involved in a collaborative, decision making sense or just handing out cash? Their role in The Club is very much 'hands on'. As Simon Jameson (chief advisor on brand strategy at C4) has stated in a recent FT article, "This is our conduit to the young creative people who are making things happen and are the type of collaborators we may need when we launch new products or services" ('Young at Art', Alice Rawsthorn. FT 'The Business' supplement, April 14, 2001). The conduit metaphor also extends to providing creative and cultural oxygen to the corporate sector with Deutsche Bank, for example, commissioning new projects from digital design companies it has met at The Club (including Digit, Tomato and Convergent Technologies) and others having received 'helpful' advice from Cap Gemini and Channel 4.

But we can all rest assured. As Sarah Duke (ICA press office) has recently pointed out, the ICA does not encourage relationships between suits because they are not a commercial networking group like First Tuesday. I quote, "The Club has got to be about creative projects as much as commercial ones. This is the ICA after all"...

I suppose that we could begin right there – what is the ICA, after all? Very simply put: we have a situation where commercial activity is being harnessed in a non-commercial environment, where a publicly funded institution has become a creative and cultural service provider to big business with little or no public debate, transparency or accountability. Sadly, I'm not a member so I'm going to swiftly move onto the second of my three models – fig 1.

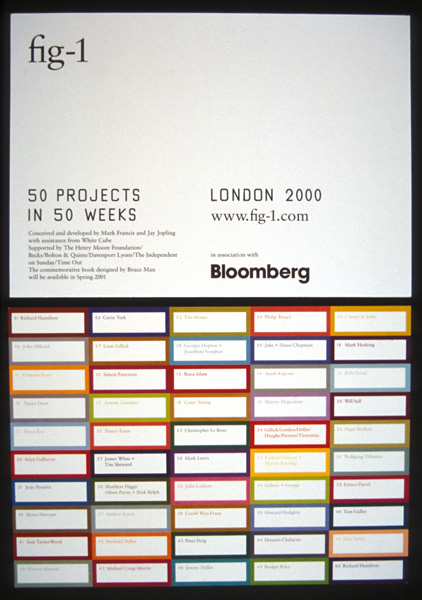

· Slide: fig-1 press release disclaimer, 2000.

fig-1, the former website and project space was another new type of alliance, but in this case funded entirely by the private sector. It was set up by independent curator, Mark Francis, gallerist Jay Jopling, and financed by Bloomberg, the financial information and services company. Given such a collaboration, the claim to be simultaneously "in association with" Bloomberg and "independent, non-profit [and] free from institutional and commercial obligations" seems curiously paradoxical. Unless of course, we now accept that the private sector is the custodian of non-profit organisations and the arbiter of 'freedom' and autonomy.

· Slide: fig-1

programme sheet 50 projects in 50 weeks, 2000.

fig-1 differed from The Club in that it remained linked to cultural presentations and exhibitions but the focus was on the broader creative industries not just the art world. So we see the writer and journalist Will Self, designers Philip Treacy, Bella Freud and Hussein Chalayan. We also see Patti Smith alongside yBa stalwarts Tracy Emin, Sam Taylor Wood and Gavin Turk.

With fig-1 we're looking at a 1 year project that claimed to be "a dynamic model for the presentation of creativity in the city" but for whom? this sounds curiously like public sector speak. fig-1 was also non-profit – it didn't sell artists' work. So what exactly was it doing? We know that it was funded and supported entirely by the private sector, but why would a private gallery and a financial services company want to build "a dynamic model for the presentation of creativity in the city"? and if so, can every City have one? We can also look at this another way – what service did fig-1 provide? Its remit was strikingly similar to the many artist-run-spaces that seem to have disappeared, or worse, been paralysed/institutionalised over the last few years. Many of these were by definition, 'dynamic models of creativity'. I think we're looking at a hybrid space, somewhere between a public institution, an artist-run-space, a gallery and a networking club funded by the private sector. More worryingly, we may be looking at another embryo or prototype – in this case, hilariously, the private-sector-financed-artist-run-space (verbal aside – Charles Saatchi the Victor Kiam of the art world "I liked the art so much I bought up the infrastructure", eg Saatchi Underwood Street Gallery and the Saatchi educational award).

For all intents and purposes fig-1 was a phantom organisation and if we look at it simply in terms of 'knowledge' – it operated as a relatively risk free satellite organisation for White Cube and cultural scratch-and-sniff site for Bloomberg. In this respect we should bare in mind Bloomberg's 'entrepreneur network' and some of the political and social projects that they have organised parties for. Despite sponsoring 'Protest & Survive' at the Whitechapel and numerous other art exhibitions they recently won the Financial Times Sponsor of the Year award for their involvement with the Royal Court Theatre (funding cut-price seats for young people). The fig-1 project came to an end in January this year having reached its objective of 50 projects in 50 weeks and the catalogue was to have been launched in association the Tate Magazine at the Venice Biennale – the same Biennale in which Bloomberg sponsored the British Pavilion and ... after show party.

The Club and fig-1 are relatively good examples of complex organisations emerging in London. Both are post-gallery and post-institutional in the sense that they are public sector/private sector hybrids defined by cross sectoral alliances and agendas. Critically, neither sell art – both trade knowledge and services.

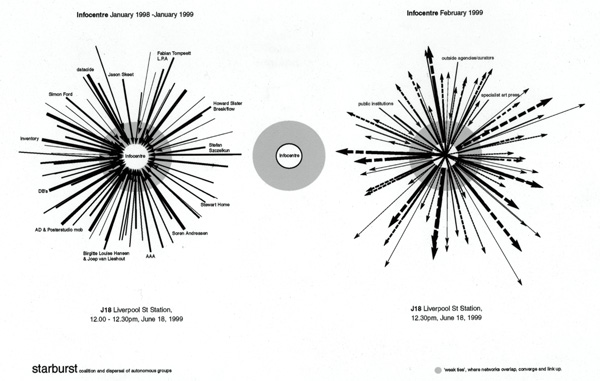

· Slide: Info Centre entrance, 1999.

Finally, I'm going to present my third and final model (Info Centre and Infopool), not as an alternative to the forms of organisation that I've just outlined but as operating within a similar set of social and cultural co-ordinates. Info Centre was an artist run project space set up by Jakob Jakobson and Henriette Heise in January 1998 (funded by the Danish Contemporary Art Foundation). It engaged and serviced a range of communities, discourses and networks in London before closing in January 1999.

· Slide: Info Centre 'starburst' diagram, 1999.

I first came across 'starburst' in a report by the City of London police into the J18 Carnival against Global Capitalism in June 1999. It is a feature of the networked protest coalitions and a strategy that had been identified by Commissioner Perry Nove as instrumental in the collapse of the command and control structure of the City of London and Metropolitan Police force on June 18. It's pretty straightforward and linked to a rapid, multi-directional dispersal from a centre or location. With Info Centre a similar starburst occurred as a result of having set up a programme for a specified period and then re-routing the networks and discourses to other locations – which, in this case, include the Infopool meetings, publications and website... and Copenhagen Free University (CFU).

· Slide: Infopool booklets 1-3, 2000.

I just want to momentarily repeat my earlier quote.. "A company is no longer really a place: it is becoming a network to which its people, its world must remain connected. Its main lever of growth is its inventory of skills and its ability to deploy them in different markets."... and suggest that, in many respects, this has been mirrored and modified in oppositional cultures and communities.

· Slide: Copenhagen Free University invite/booklet, 2001

These 'forms' are not necessarily innovative in terms of cross sectoral alliances. If anything they represent a different set of relations to the landscape that I've just outlined. They share a common point of reference with The Club and fig-1 in that knowledge, alliances and networks are central to their programmes but the Copenhagen Free University, for example, rejects (and I quote) "the so-called knowledge economy as the framing understanding of knowledge" (Copenhagen Free University, May 15, 2001). We could ask ourselves what alternative form of exchange and economy they propose? and where my role as a speaker/participant falls within the 'understanding (and deployment) of knowledge'?

I think that these strategies can be seen within the context of withdrawal and exit, a reassessment of cultural capital, knowledge and services. In this sense they share something in common with many networks in London (and I'm sure here in Copenhagen) that are currently re-configuring themselves into closed forums, assemblies, small gatherings and clubs. For many artists, organisations and individuals on the 'frontline', particularly those forging new relationships and economies with the private sector, this is not an option – there is no withdrawal, only degrees of convergence. But both can be seen within the context of a general collapse in confidence in the public sphere, exacerbated by a lack of corporate transparency and the increasingly suspect channels of communication and exchange offered by public institutions.

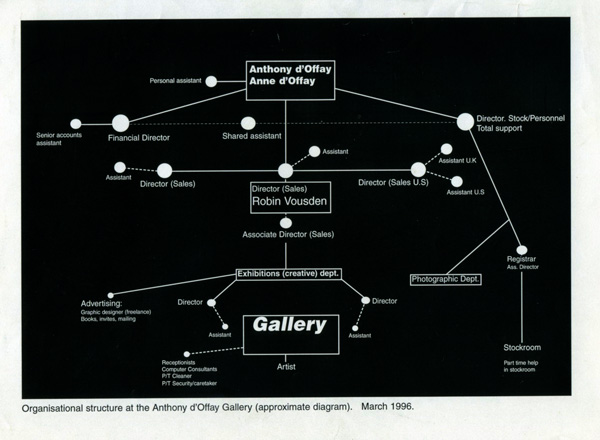

· Slide: Anthony d'Offay diagram, staff structure. Posterstudio, November 1996.

Finally, and this is my scripted joke. In celebration of the blue-chip gallery (we all know and love) that announced its closure a couple of weeks ago – I thought I'd end by showing you a rigidly hierarchical structure, the type that we now associate with the inflexibility of the 'old' economy. I very much hope that I have laid out a field in which we can begin to consider some of the questions that have emerged in our professions, practices and institutions.

Anthony Davies (The Ian Burn Appreciation Society) for the CFU, 29.09.01.

* This presentation has been compiled from research material produced in association with Simon Ford.